Showing posts with label idioms and phrases. Show all posts

Showing posts with label idioms and phrases. Show all posts

07 March 2018

Litmus test

Litmus is a water-soluble mixture of different dyes extracted from lichens. The word comes from lytmos and Old Norse litmosi meaning dye-moss. The main use of litmus is to test whether a solution is acidic or basic. It is often absorbed onto filter paper to produce one of the oldest forms of pH indicator. Litmus turns red under acidic conditions and blue under alkaline conditions.

The more modern figurative use of the term "litmus test" is a situation in which you arrive at a conclusion based on a single factor, such as an attitude, event, or fact) is decisive. A headline such as "Eurozone Elections: Litmus Test for the EU" is an example of that usage.

22 January 2018

P.U.

How did "P.U." get to be used to mean that something smelled bad?

Though it is sometimes spelled "piu," I always hear it pronounced as "pee-yew" with the two syllables often stretched out - and perhaps accompanied by a inched nose.

It is not an expression that is used as much these days. I associate it with my mother's generation. But actually, it is a lot older than that.

In the 1600s, the expression of a foul odor was pyoo. But English spelling had not become standardized, so this expression of disgust was also written as pue, peugh, pew and pue - but always pronounced as pyü. In our time, P.U. is the more common spelling.

This expression's root igoes back to the Indo-European word pu meaning to rot or decay. It is a shortened version of puteo, which is Latin for "to stink, to smell bad."

Though it is sometimes spelled "piu," I always hear it pronounced as "pee-yew" with the two syllables often stretched out - and perhaps accompanied by a inched nose.

It is not an expression that is used as much these days. I associate it with my mother's generation. But actually, it is a lot older than that.

In the 1600s, the expression of a foul odor was pyoo. But English spelling had not become standardized, so this expression of disgust was also written as pue, peugh, pew and pue - but always pronounced as pyü. In our time, P.U. is the more common spelling.

This expression's root igoes back to the Indo-European word pu meaning to rot or decay. It is a shortened version of puteo, which is Latin for "to stink, to smell bad."

03 January 2018

Over the Ether

In ancient and medieval times scholars and philosophers believed that there was a medium which filled out the space of the universe. This medium was called aether or ether, or also quintessence.

Ethers are definitely a class of organic compounds that contain an ether group—an oxygen atom connected to two alkyl or aryl groups. But "ether" is a word that can mean several things.

Ether can refer to the upper regions of space.

It was once used as the name of a common surgical anesthetic.

Ether, or luminiferous Ether, was the hypothetical substance through which electromagnetic waves travel. It was proposed by the greek philosopher Aristotle and used by several optical theories as a way to allow propagation of light, which was believed to be impossible in "empty" space.

The brilliant and erratic Nikola Tesla believed that electromagnetic waves propagate in aether and that gravitational and magnetic forces are all directly related to the aether.

It took many years and many experiments, but now we know that, based on scientific evidence, electromagnetic waves do not need a medium to travel through. The existence of ether was not found in the Michelson-Morley experiment performed in 1887, and the the then-prevalent aether theory fell away. Heading in another direction, research eventually led to special relativity, which rules out the existence of aether.

But despite that research in the early days of radio, "over the ether" was a phrase used to refer to radio airwaves, as when a signal comes over the ether.

Radio waves are electromagnetic radiation and, unlike sound waves which require material to vibrate and reflect energy to be heard, radio waves are received by being caught by an antenna. They can then be focussed and amplified using a tuner and amplifier system.

29 December 2017

Flick Lives

“Flick Lives” is a reference to a character in many stories by radio humorist and writer Jean Shepherd. Flick was one of Shepherd's childhood friends tales from his Indiana days. You might know him as the kid who gets his tongue frozen to a pole in the film A Christmas Story.

Fans and listeners to Shepherd's WOR-AM late night radio show in New York would often write “FLICK LIVES” as graffiti. Like the way that soldiers during WWII once wrote “Kilroy was here,” it was not only a way of marking your turf, but also show that your were one od Shep's "night people."

Yes, people used to sometimes join the L and I in Flick to create a totally different message to the world.

Poor Flick gets his tongue frozen to an icy metal pole in A Christmas Story

15 November 2017

Boomerang Generation

The term can also be used to indicate only those members of this age-set that actually do return back home and not the whole generation. In as much as home-leaving practices differ by economic class, the term is most meaningfully applied to members of the middle class.

16 October 2017

Cock and Bull Stories

Signs for the two inns -- via Cnyborg/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 3.0

A "cock and bull" story is one that is rather unbelievable. The most common origin is that the phrase is connected to two inns in Stony Stratford, England.

Stony Stratford ("the stony ford on the Roman road") was an important stop for coaches in the 18th and early 19th centuries that carried mail and passengers en route to and from London to northern England.

One version of the etymology says that rivalry between groups of travellers resulted in exaggerated and fanciful stories told on those coaches and in the two inns in town which became known as 'cock and bull stories'.

The inns are real (signs for them above). Both were on the coach road (A5 or Watling Street). The Cock Hotel is documented to have existed in one form or another on the current site since at least 1470. The Bull existed at least before 1600.

The second most common origin story is that these stories were another form of folk tales that featured magical animals, such as found in Aesop's fables or The Arabian Nights.

The early 17th century French term coq-a-l'âne ("rooster to jackass") is sometimes mentioned as the origin and that it was imported into English, though I found little evidence for this. However, the Lallans/Scots word "cockalayne" with the same type of meaning does appears to be a direct phonetic transfer from the French.

I wondered if there is any connection to the words poppycock and bullshit.

"Poppycock" appears to be a much more recent mid-19th century Americanism. It might comes from the Dutch pappekak, which literally does mean dung or excrement, whether from a bull or not.

Poppycock tends to be used for pretty lightweight nonsense, while bullshit has the stronger sense of the intention of deceiving or misleading.

"Bullshit," once considered taboo and an expletive, seems more acceptable these days. It is also an Americanism from the early 20th century. It may have a connection to the Middle English word bull.

The idiom "shoot the bull", meaning to talk aimlessly, was used in 17th century. It came from Medieval Latin bulla meaning to play, game, or jest. You still hear people use the shorter and more acceptable "bull" to mean bullshit, as well as the shorter and even less acceptable "shit" to mean the same thing.

19 September 2017

Halt and Catch Fire

Halt and Catch Fire is an American drama television series about a fictionalized version of the history of the personal computer revolution of the 1980s and then the growth of the World Wide Web in the early 1990s.

The show's title refers to a computer machine code instruction abbreviated as HCF. Halt and Catch Fire refers to a computer machine code instruction that causes the computer's central processing unit (CPU) to cease any meaningful operation to the point of requiring a restart of the computer.

Originally it referred to a fictitious instruction in IBM System/360 computers. Later, the joke became real when developers actually wrote such code.

Usually, when a computer hits a bug in the code it probably can still recover, but an HCF instruction is one where there is no way for the system to recover without a restart. It halts the computer, but the "catch fire" part is not literal. There is no computer bursting into flames. The exaggeration was that the circuits would be switching so fast that they would overheat and burn.

04 September 2017

Rosetta Stone

The term "Rosetta stone" has been used to represent any crucial key in the process of decryption of encoded information. This is especially true when only a small but representative sample is recognized as being the clue to understanding a larger whole.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first figurative use of the term appeared in 1902. In H. G. Wells' 1933 novel The Shape of Things to Come, a manuscript written in shorthand provides a key to understanding additional material sketched out in both longhand and on typewriter.

Theodor W. Hänsch wrote in 1979 that "the spectrum of the hydrogen atoms has proved to be the Rosetta stone of modern physics" and understanding the key set of genes to the human leucocyte antigen has been described as "the Rosetta Stone of immunology."

The original Rosetta Stone is a black granodiorite (an igneous rock similar to granite) slab that was found in 1799. It is inscribed with three versions of a decree issued at Memphis, Egypt in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty on behalf of King Ptolemy V.

Because the top and middle texts are in Ancient Egyptian (using hieroglyphic script and Demotic script, respectively) while the bottom is in Ancient Greek, the Rosetta Stone proved to be the translation key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Carved during the Hellenistic period, it is believed to have originally been displayed within a temple, but was probably moved during the early Christian or medieval period. It was rediscovered in 1799 as part of a the building material in the Fort Julien near the town of Rashid (Rosetta) in the Nile Delta by a French soldier during the Napoleonic campaign in Egypt.

Lithographic copies and plaster casts were made for European museums and scholars to study.

It has been on public display at the British Museum almost continuously since 1802 and is the most-visited object there, but ever since its rediscovery, the stone has been the focus of nationalist rivalries, including its transfer from French to British possession during the Napoleonic Wars, and demands for the stone's return to Egypt.

Some readers will know the term Rosetta Stone used as the title of translation and language-learning software published by Rosetta Stone Ltd.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the first figurative use of the term appeared in 1902. In H. G. Wells' 1933 novel The Shape of Things to Come, a manuscript written in shorthand provides a key to understanding additional material sketched out in both longhand and on typewriter.

Theodor W. Hänsch wrote in 1979 that "the spectrum of the hydrogen atoms has proved to be the Rosetta stone of modern physics" and understanding the key set of genes to the human leucocyte antigen has been described as "the Rosetta Stone of immunology."

| |

| The Rosetta Stone in the British Museum - by © Hans Hillewaert, CC BY-SA 4.0 |

The original Rosetta Stone is a black granodiorite (an igneous rock similar to granite) slab that was found in 1799. It is inscribed with three versions of a decree issued at Memphis, Egypt in 196 BC during the Ptolemaic dynasty on behalf of King Ptolemy V.

Because the top and middle texts are in Ancient Egyptian (using hieroglyphic script and Demotic script, respectively) while the bottom is in Ancient Greek, the Rosetta Stone proved to be the translation key to deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs.

Carved during the Hellenistic period, it is believed to have originally been displayed within a temple, but was probably moved during the early Christian or medieval period. It was rediscovered in 1799 as part of a the building material in the Fort Julien near the town of Rashid (Rosetta) in the Nile Delta by a French soldier during the Napoleonic campaign in Egypt.

Lithographic copies and plaster casts were made for European museums and scholars to study.

It has been on public display at the British Museum almost continuously since 1802 and is the most-visited object there, but ever since its rediscovery, the stone has been the focus of nationalist rivalries, including its transfer from French to British possession during the Napoleonic Wars, and demands for the stone's return to Egypt.

Some readers will know the term Rosetta Stone used as the title of translation and language-learning software published by Rosetta Stone Ltd.

22 May 2017

Mind Your P's and Q's

Has anyone ever advised you to "mind your p's and q's"? If you were in England, they meant to be on your best behavior, and if in America they meant to pay close attention. They probably did not mean to watch out how you set your type for a printing press, but that is the origin of that phrase.

We actually get a good number of words and phrases borrowed from the print shop. The book Printer’s Error: Irreverent Stories from Book History is an entertaining history of printed books, authors and printers that gives us many examples.

One example is "minding your p's and q's" which is a phrase that comes from the printing process in the days past when physical movable type was used in a printing press.

I actually had the opportunity in my youth to set some type for printing. Setting type means placing each individual metal letter or symbol in a tray backward, so that when the inked type is pressed into paper, the mirror image reads the right way forward.

This was the job of compositors who had to be very careful setting up lines and pages of type - especially when it came to letters that look like mirror images of each other.

In older type cases (such as the one seen above and below), each letter was kept in its own section to be picked out by the compositor. The letters "b" and "d" could be confusing, but the lowercase p’s and q’s were right next to each other. "Mind your p’s and q’s” quite literally meant to be careful with those letters.

In that type case. all the capital letters are on the top or in a second upper case. The ones in the lower part of the case are what we began to call lowercase letters.

|

| Upper and lower cases of type |

09 March 2017

Riding Shotgun

|

| John Wayne riding shotgun in Stagecoach |

The usage has its roots in a bygone era of the American West when stagecoaches were common. At least in the retelling of American history through films and television, we learned that back in the 1880s the seat next to the driver on top was given to someone with a gun.

Though shotguns offered the chance to hit one or more attackers more easily from a bouncing seat, we also have seen on the screen men with rifles and pistols riding shotgun. The term became a generic way of describing the seat and the duty.

The phrase appears in the 1939 John Ford film Stagecoach starring John Wayne who declares that “I’m gonna ride shotgun.” Randolph Scott starred in a 1954 film titled Riding Shotgun.

Though we hope no one today who calls shotgun when getting into a car is carrying a weapon, the term has survived in slang usage. In the 21st century, riding shotgun might require monitoring the GPS and answering phone calls and text messages for the driver, which are jobs that might actually save the driver's life.

03 October 2016

Abracadabra

Abracadabra is an incantation used, primarily in stage magic tricks for entertainment purposes.

But in its origin story was an ancient belief that the incantation had healing powers.

The word's origin is not clear, but it is often listed as Aramaic from a phrase meaning "I create as I speak." The etymology is not confirmed. Wikipedia says that the phrase in Aramaic אברא כדברא would be more accurately translated as "I create like the word."

The origin stories are numerous: an abbreviated forms of the Hebrew words for "father, son, holy spirit,"; a reference to Abraxas, a god worshiped in Alexandria in pre-Christian times.

The first known mention of the word was in the third century AD in a book called Liber Medicinalis by Quintus Serenus Sammonicus, physician to the Roman emperor Caracalla. It was he who prescribed wearing an amulet containing the word written in the form of a triangle for several lethal diseases.

It was used by the Gnostics of the sect of Basilides, and is found on Abraxas stones, which were worn as amulets.

The Puritans dismissed the word as having any power, but some Londoners posted the word on their doorways to ward off sickness during the Great Plague of London.

English occultist Aleister Crowley believed it had power and used the spelling abrahadabra.

Today, it is best known as it is used by stage magicians when performing a trick. It is also common in the popular culture in comic books, games, music, film and television and literature.

J.K. Rowling said in a talk in 2004 that the incantation Avada Kedavra in her Harry Potter books (known as the "killing curse") "is the original of abracadabra, which means 'let the thing be destroyed.' Originally, it was used to cure illness and the 'thing' was the illness, but I decided to make it the 'thing' as in the person standing in front of me. I take a lot of liberties with things like that. I twist them round and make them mine."

05 September 2016

Internet Versus World Wide Web

Twenty-five years ago (23 August 1991), the World Wide Web first went public when Tim Berners-Lee, a British scientist working at CERN, granted the general public access to the web for the first time. Despite confusions about this, it was not the start of the Internet.

What Tim did allowed less technical computer users to get on the Internet in a simple way. Some people call August 23 Internaut Day ('internaut' being a portmanteau of 'internet' and 'astronaut' – an early reference to technically able internet users).

Many people think the internet and the World Wide Web are the same thing – but they are different systems.

The Internet is a network of computers that are connected.

The World Wide Web refers to the web pages found on this network of computers. Your web browser uses the Internet in order to access the web.

Some chronology:

Tim Berners-Lee is now the director of the World Wide Web Consortium, which works to develop the Web. It is abbreviated WWW or W3C.

What Tim did allowed less technical computer users to get on the Internet in a simple way. Some people call August 23 Internaut Day ('internaut' being a portmanteau of 'internet' and 'astronaut' – an early reference to technically able internet users).

Many people think the internet and the World Wide Web are the same thing – but they are different systems.

The Internet is a network of computers that are connected.

The World Wide Web refers to the web pages found on this network of computers. Your web browser uses the Internet in order to access the web.

Some chronology:

- 12 March 1989, Berners-Lee submitted a proposal for a "distributed hypertext system" that would allow scientists at CERN, the renowned particle physics laboratory in Switzerland, to share data from experiments across networks. He was using a NeXT computer, which was one of Steve Jobs' early products.

- October 1990, Berners-Lee began working on the world's first web browser, called WorldWideWeb – but it was later renamed Nexus so not to cause confusion between the WorldWideWeb (the software) and the World Wide Web (the information space).

- August 1991, the first website went online: http://info.cern.ch (check it out - they have preserved some cool things there)

- April 1993, World Wide Web technology was made available to all for free. "CERN relinquishes all intellectual property rights to this code, both source and binary and permission is given to anyone to use, duplicate, modify and distribute it," a statement read.

Tim Berners-Lee is now the director of the World Wide Web Consortium, which works to develop the Web. It is abbreviated WWW or W3C.

22 August 2016

cutting, leading and bleeding edges

Companies all want to be at the edge. The university I teach at, NJIT, has as it's tagline "At the edge of knowledge." I always thought it was an odd line because being at the edge seems to be not quite there. Of course, it is playing off the terms leading edge, bleeding edge and cutting edge. Are they all the same edge?

The cutting edge (also cutting-edge when used as an adjective) had a quite literal meaning back in the early 1800s of being the edge of a blade, especially in reference to plows. The more modern and figurative use appeared in the mid-1800s. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines it as “A dynamic, invigorating, or incisive factor or quality, especially one that delivers a decisive advantage. Hence: the latest or most advanced stage in the development of something; the forefront, especially of a movement.” I suppose the idea is of a blade making a clean cut through what we know (norms, expectations, barriers) to new ground.

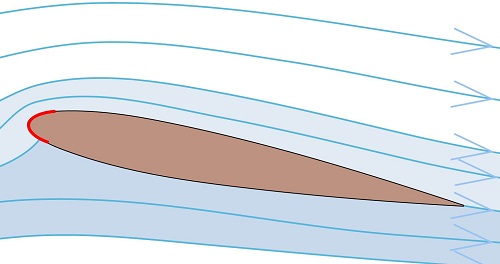

“Leading edge” (noun or also adjective) appeared in the 19th century. Again, it had a literal meaning similar to that knie or plow edge with it being the forward edge of the blade of a screw propeller that you would find on a ship. That would be the part that cuts through the water. It also referred to the edge of an airfoil on an airplane wing that faces the direction of motion.

Usages such as being on the "leading edge of technology" became common. I also found it to mean during WWII the “upswing” of an electrical pulse.

Appearing more recently (the 1980s) was the term “bleeding edge.” It seems to be just another version of the two previous terms which are often used interchangeably, combining the knife cutting image (bleeding) with the other figurative uses. However, it seems to be distinguished in its usage by the idea that something on the "bleeding edge" is very advanced but still quite experimental. It may be a technology that has no current practical application. That is something that can be risky. The word “bleeding” is sometimes used in reference to a financial loss. I would say that the bleeding edge is something that is beyond, perhaps not in a positive sense, the cutting edge.

|

| plow via wikipedia.org |

The cutting edge (also cutting-edge when used as an adjective) had a quite literal meaning back in the early 1800s of being the edge of a blade, especially in reference to plows. The more modern and figurative use appeared in the mid-1800s. The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) defines it as “A dynamic, invigorating, or incisive factor or quality, especially one that delivers a decisive advantage. Hence: the latest or most advanced stage in the development of something; the forefront, especially of a movement.” I suppose the idea is of a blade making a clean cut through what we know (norms, expectations, barriers) to new ground.

“Leading edge” (noun or also adjective) appeared in the 19th century. Again, it had a literal meaning similar to that knie or plow edge with it being the forward edge of the blade of a screw propeller that you would find on a ship. That would be the part that cuts through the water. It also referred to the edge of an airfoil on an airplane wing that faces the direction of motion.

Usages such as being on the "leading edge of technology" became common. I also found it to mean during WWII the “upswing” of an electrical pulse.

Appearing more recently (the 1980s) was the term “bleeding edge.” It seems to be just another version of the two previous terms which are often used interchangeably, combining the knife cutting image (bleeding) with the other figurative uses. However, it seems to be distinguished in its usage by the idea that something on the "bleeding edge" is very advanced but still quite experimental. It may be a technology that has no current practical application. That is something that can be risky. The word “bleeding” is sometimes used in reference to a financial loss. I would say that the bleeding edge is something that is beyond, perhaps not in a positive sense, the cutting edge.

15 June 2016

Mum's the Word

|

| A WWII poster using the phrase |

“Seal up your lips, and give no words but mum.” - Henry VI (1:2)

A friend used the expression “mum’s the word” and it made me wonder about its origin. I guessed that "mum" might be some British reference to mother, although the connection to being quiet was not there, other than -mother telling you to be quiet. In its usage, the phrase always seems to have a secretive association.

The expression dates from about 1700, but mum, which means “silence,” is much older. That goes back to around 1350 and the Middle English word momme for silence.

It might also be derived from the "mummer," a person who does pantomime and acts without saying anything.

There is a phonetically similar German word "stumm" (Old High German "stum", Latin "mutus") meaning "silent, mute".

We use the phrase as a request or warning to say nothing, often to not reveal a secret.

30 May 2016

Snake Oil

Once upon a time there were bottles of snake oil. Now, it exists only in a figurative sense.

Historically, snake oil came to America via the Chinese laborers who were building the transcontinental railroad. For them, snake oil was a traditional folk liniment used to treat joint and muscle pain that actually had a connection to snakes (venom).

Rival American "medicine" salesmen used the term generically for things marketed as miraculous remedies whose ingredients were usually secret, and it was definitely a negative term.

Some of that snake oil and those other "medicines" were effective, though it might have been a placebo effect. But that's true of many modern quick cures too.

23 May 2016

Shoot the Moon

"Shoot the moon" is an English idiom. A hundred years ago, it was similar to the phrases "bolt the moon" or "a moonlight flit" or even the older "shove the moon" which are now obsolete. It meant to remove one’s household goods by "the light of the moon" in order to avoid paying the rent or to avoid one’s creditors. This British expression also applied to other stealthy departures or a related action to sneak, abscond, take flight without meeting one’s responsibilities.

Today, when someone says that someone will "shoot the moon" is to go for everything or nothing. It is similar to the phrases "to go for broke,""to go whole hog," and "to pull out all stops." In all cases, one would take a great risk.

The idiom suggests that there is as much of a chance of success as there is shooting (a bullet, arrow etc.) and hitting the Moon.

the moon with a arrow or rifle bullet – set one’s sights high and trying for something that one wants badly, but for which realistically the probability of success is not good.

"Shoot the moon"comes from the card game ‘hearts.’ Hearts is a point-based game and most of the time the goal is to acquire the least number of hearts possible. But if you choose to risk shooting the moon and wins all the hearts and the queen of spades in the course of play, you can deliver a crushing blow to their opponents. However, if this move fails, you put yourself in an almost irrecoverable position.

I'm not a card player and I came upon the term through a 1982 movie Shoot the Moon starring Albert Finney and Diane Keaton.It's a good but depressing film about a marriage falling apart. The director, Alan Parker, is British and the film's writer, Bo Goldman, is American, so I'm not sure if the old British or modern definition applies to the film. The husband would like to skip out on his marriage. Is it about a time in the marriage when it's "all or nothing?" Unclear to me.

10 March 2016

God Bless You and the Sneeze

God bless you (also "God bless" or "Bless you")is a common English response to to a sneeze.

The phrase has been used, not for sneezes, in the Hebrew Bible by Jews (cf. Numbers 6:24), and by Christians, since the time of the early Church. Generally, it was meant as a benediction, as well as a means of bidding a person "Godspeed," an expression of good wishes or good luck to a departing person or a person beginning a journey.

During the plague of AD 590, Pope Gregory I ordered unceasing prayer for divine intercession. Part of his command was that anyone sneezing be blessed immediately by saying "God bless you." Sneezing was often the first sign that someone was falling ill with the plague.

By 750, during a plague outbreak or not, it became customary to say "God bless you" as a response to one sneezing. It was once thought that sneezing was an omen of death, since many dying people fell into sneezing fits.

Not all sneezing had negative connotations. Later, the Hebrew Talmud called sneezing “pleasure sent from God.” The Greeks and Romans believed that sneezing was a good omen and responded to sneezes with “Long may you live!” or “May you enjoy good health.”

It is still seen as a sign of good fortune or God's beneficence in some cultures, as seen in the German word Gesundheit (meaning "health") sometimes adopted by English speakers, and the Irish word sláinte (meaning "good health"), the Spanish salud (also meaning "health") and the Hebrew laBri'ut (colloquial) or liVriut (classic) (both spelled: "לבריאות") (meaning "to health").

See also: wikipedia.org/wiki/Responses_to_sneezing

09 October 2015

Cloud Nine

|

| cumulonimbus cloud |

I never gave thought about its origin before, but I was reading about, oddly enough, contemplative prayer The Cloud of Unknowing) and a reference was made to cloud nine as something from Buddhism.

I have to say that my own associations with the term are more with the "psychedelic soul" song, "Cloud Nine," by The Temptations

Looking for the etymology, I found most frequently references to Buddhism and to the study of clouds.

There is an actual (but old) International Cloud Atlas which defines types of cloud. (Not to be confused with Cloud Atlas: A Novel

In Buddhism, it supposedly is a reference to the state of being that is the penultimate goal of the Bhodisattva.

A flaw in both these origins is that there are ten stages in the progress of the Bodhisattva, and there are actually ten levels of clouds.

Another reference is to in Dante's Paradise section of the Divine Comedy where the 9th level of heaven is closest to the Divine Presence, which itself dwells at the 10th and highest heaven.

In all three instances 9 is not the top.

Another pop culture reference I found is to a 1950s radio show called "Johnny Dollar" in which every time the hero was knocked unconscious he was transported to Cloud Nine. The 1950s fits in with the Cloud Atlas of that period, but there are earlier references to cloud nine.

I suppose that if the old atlas only had 9 levels, that may have influenced the usage. I can think of other "nine" references in our popular usage where the nine seems an odd choice. There is the 'whole nine yards' in American Football, where it is ten yards rather than nine that is a significant measure for a first down. And we also say someone is "dressed to the nines" as being very fancily dressed.

It seems that even earlier the phrase "head in the clouds" to mean a kind of dreaminess, induced by either intoxication or inspiration, was used. A 1935 directory of slang, The Underworld Speaks, gives the examples of "Cloud eight, befuddled on account of drinking too much liquor."

The Dictionary of American Slang (1960) might be the first printed definition of the term cloud nine as we use. At that point in time, the term had close association with the euphoria that is induced by alcohol and drugs.

24 July 2015

à la mode

|

| Traditional pie à la mode - vanilla ice cream on apple pie. |

I had a recent argument with two colleagues about pie à la mode. We did not agree on whether or not the ice cream can be placed beside the pie, and we disagreed on whether or not flavors other than vanilla are acceptable. (FYI: I say yes to both of those.)

But we might also ask why is a dessert with ice cream called à la mode?

Therefore, I was delighted to see that the lofty Oxford Dictionary folks did a post on that last question.

The New York Times credits the spread of this term to Charles Watson Townsend. His 1936 obituary reported that after ordering ice cream with his pie at the Cambridge Hotel, in the village of Cambridge, New York, around 1896, a neighboring diner asked him what this wonder was called. “Pie à la mode,” Townsend replied. When Townsend subsequently requested this dessert at the famous Delmonico’s restaurant in New York City, the staff had no idea what it was. Townsend inquired why such a fashionable venue had never heard of pie à la mode. Bien sûr, the dessert found its way onto Delmonico’s menu and requests for it soon spread.The French expression translates simply as "in a style or fashion" and, when it came to food, it referred to a traditional recipe for braised beef, which at one time was considered a new fashion.

Oxford says that there was also some evidence that John Gieriet of Switzerland had previously invented the dessert in 1885 while proprietor of the Hotel La Perl in Duluth, Minnesota, where he served the ice cream with warm blueberry pie.

12 June 2015

The Funny Bone

Ever hit your "funny bone"? It's not funny. It hurts.

And it's not a bone either.

What is known as the funny bone is actually a nerve - the ulnar nerve - that runs from your neck all the way to the hand. Commonly, people will whack their elbow on something and the pain will radiate along that path right down to your pinkie and ring finger.

Our nerves are shielded in most cases by bones, muscles and/or ligaments. That is true of the ulnar too EXCEPT at the point where it passes the elbow through a channel called the cubital tunnel. The only protection there is skin and fat, so it is quite vulnerable.

A decent bump there on the corner of some furniture hits the nerve against bone and sends some pain down the forearm and hand.

So, why call it a "funny bone"?

There seems to be a two-part answer. The ulnar nerve runs along a bone called the humerus (homonym for "humorous") and at one time it may have been believed that it was that bone that was reacting.

It might also be that "funny" was used in its non-humorous sense of "odd" as in having a funny feeling about something.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)